Since the introduction of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), clinical remission has become an achievable therapeutic goal for many patients with chronic rheumatic diseases.1-3

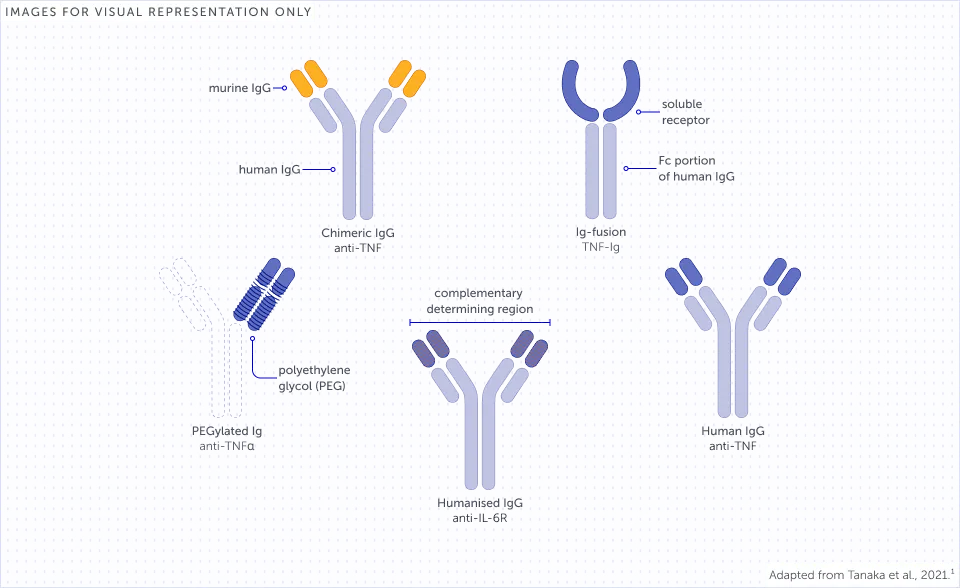

bDMARDs have mechanisms of action (MoAs) that inhibit specific targets involved in disease pathogenesis.1,4 These MoAs are underlaid by differing molecular structures of bDMARDs which impact how these treatments interact with immune pathways.1,4,5

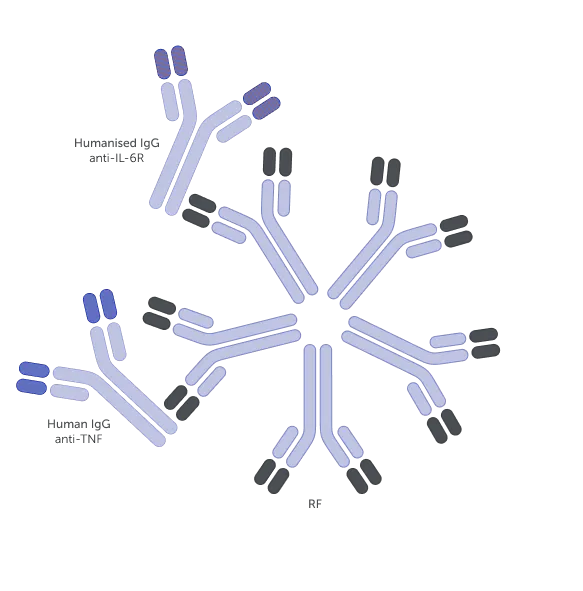

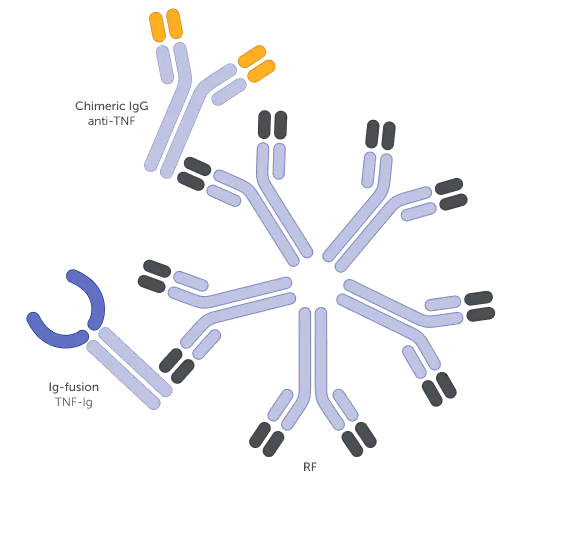

Examples of different bDMARD structures1,a

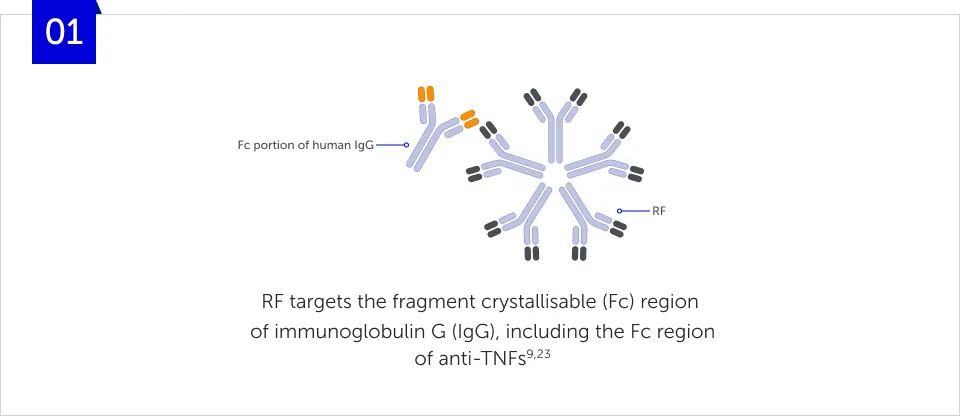

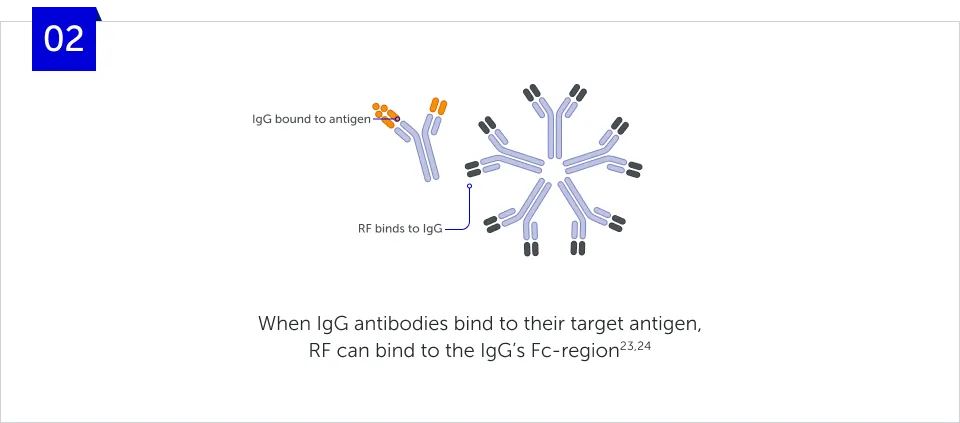

The molecular structure of a bDMARD can affect various immune processes that may underlie its function.5-7 For example, rheumatoid factors (RFs) can bind to fragment crystallisable (Fc)-containing bDMARDs, impacting their function.5,7-9 The structure of Fc-containing bDMARDs also allows them to cross the placenta, thereby potentially disrupting treatment continuity for women of childbearing age.10-12

Read on to find out more about the impact of the molecular structure of Fc-containing bDMARDs.

Immune complex formation

2 MIN READ

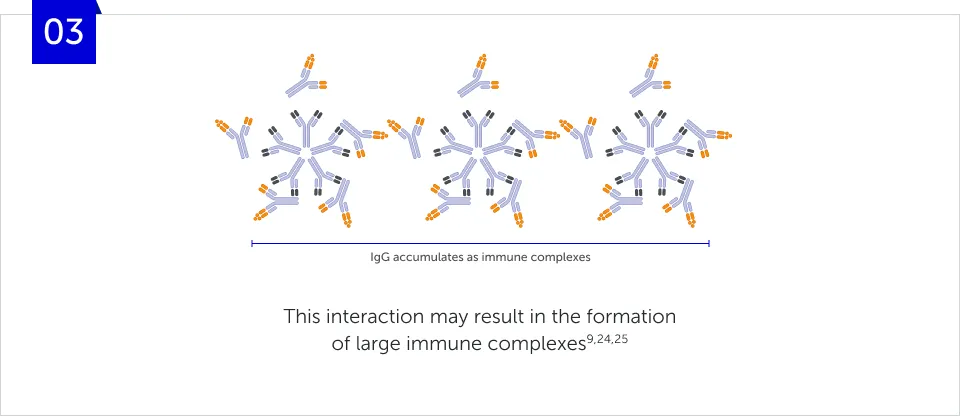

IMMUNE COMPLEX FORMATION

How does RF form immune

complexes?

IMMUNE COMPLEX FORMATION

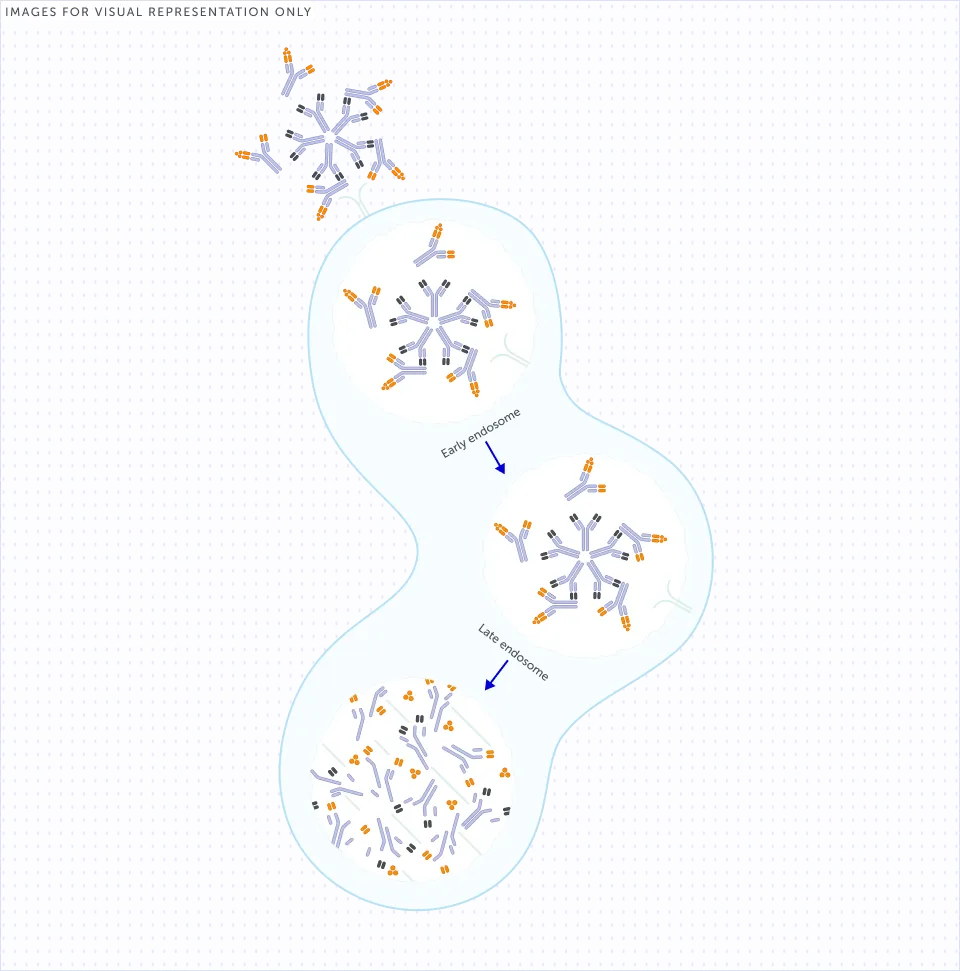

Where do RF-IgG immune

complexes end up?

Large RF-IgG immune complexes can be internalised, predominantly by macrophages through the Fc-gamma receptors (FcγRs) on their cell surface and are subsequently degraded by lysosomes.9,26 This activation of the immune system to degrade RF-IgG immune complexes attracts additional immune cells to the affected joints, thereby further increasing inflammation.8

High RF levels are associated with a decreased response to anti-TNFs containing an Fc region.17,19,20,b

Many bDMARDs used in RA

contain Fc regions27,28

How could RF-IgG immune complexes be impacting the treatment response of your patients with RA?

Clinical implications of bDMARD structure: The case of RF

2 MIN READ

High RF levels are recognised as a poor prognostic factor for RA and a predictor of responses to treatment.18-20,22 Prof. James Galloway explores how the binding of RF to the Fc region of antibodies can affect clearance of some Fc-containing biologics, which could have implications for treatment choice.7,8

“Rheumatoid factor can bind and form immune complexes with drugs that have an Fc component”

Prof. James Galloway

King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

Fc structure and its potential implications for placental transfer

2 MIN READ

Early and continuous treatment to achieve remission is recommended for women of childbearing age (18–45 years) with chronic rheumatic diseases.12,29-31 This approach helps to prevent disease progression, maintain quality of life and support future family plans.29,31-34 However, Fc-containing anti-TNFs can cross the placenta, which may necessitate further treatment-planning discussions and disrupt treatment continuity.10-12

In the video below, Dr Pluma shares her expert insights on the potential impact of placental transfer of Fc-containing bDMARDs, and how this might impact treatment planning for women of childbearing age.

“It is important to take into account both drug effectiveness and placental transfer with regards to biologic treatments used during pregnancy"

Dr. Andrea Pluma Sanjurjo

Vall d'Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain

Other articles you might like

Recommended Articles

You can read more articles that might interest you.

Find out more about how timely shared decision-making discussions can help address unmet needs for women of childbearing age.

The Role of Rheumatoid Factor in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Discover more about the role of rheumatoid factor in rheumatoid arthritis

Want to see more videos?

Can’t find the answer you’re looking for? See all the Resources we have.

GL-DA-2500784

Date of preparation: October 2025