Explore factors impacting RA and axSpA management, such as radiographic progression, and sex and gender differences.

Radiographic progression – which refers to the progressive structural damage visible on radiographic imaging – significantly contributes to the overall burden of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA).1–3 For patients, radiographic progression can mean increased damage and deterioration in the joints or spine, increased functional disability, reduced quality of life and higher healthcare costs.1–3

The majority of patients with RA experience joint damage within the first 2 years of their condition.2,12 Therefore, preventing joint damage progression is one of the primary goals of RA treatment.5,10,12,13 Regular monitoring is also required, as radiographic progression in RA can occur even in patients who have achieved disease remission.12–14

Identifying risk factors is important for preventing radiographic damage, particularly in patients with early RA, so as to inform treatment decisions and optimise treatment outcomes.15,16 One of the risk factors for radiographic progression is high rheumatoid factor (RF) levels, which are found in approximately 25% of patients with RA.16–20,a In RF-positive patients, joint destruction has been observed to progress more rapidly than in RF-negative patients.17,a Of note, high levels of RF have been associated with higher levels of RA disease activity;17,21,a while disease activity correlates with risk of radiographic progression, high RF levels have been shown to also impact joint damage independently of disease activity.19,a

High RF levels are also associated with decreased response to treatment with anti-tumour necrosis factors (TNFs) that contain a fragment crystallisable (Fc) region.17,22–24,a This is due to the ability of RF to bind Fc-containing anti-TNFs, via the Fc region, to form RF-anti-TNF immune complexes, whose clearance by macrophages may reduce the concentration of circulating anti-TNFs.5,17,22,25,26,a As a result, patients with RA and high RF levels may be less responsive to the effects of Fc-containing-anti-TNF treatment on radiographic progression.17,22–24,a

Damage caused by radiographic progression is irreversible, hence this is an important consideration during treatment to reduce the long-term impact of RA or axSpA on the daily lives of patients.4–7 To allow for appropriate monitoring, it is important to note that the clinical features of radiographic progression differ between RA and axSpA.3,8–11.

axSpA can be classified as non-radiographic (nr-axSpA) or radiographic axSpA (r-axSpA; also known as ankylosing spondylitis [AS]), where r-axSpA is defined by the presence of radiographic damage in the sacroiliac joints.11,27 Progression from nr-axSpA to r-axSpA occurs when inflammation in the sacroiliac joints progresses to structural joint damage.11,28–30

Some patients with r-axSpA also experience spinal damage.27 Progression in the spine can lead to loss of spinal mobility and reduced physical functioning, impacting patients’ ability to complete daily activities and their overall quality of life.3,30 Radiographic progression is therefore a major concern in the management of axSpA, as it can lead to irreversible structural damage and functional impairment.1,30

When considering the clinical aspects of axSpA more broadly, it is also important to consider sex- and gender-associated differences which can impact the diagnosis and disease management of female patients.7,31–33 This is particularly important when treating women of childbearing age, who experience greater diagnostic delay compared to men, and for whom early and continuous treatment is recommended.31–40

Read on to find out more about the impact of high RF levels on radiographic progression in RA, how this differs from radiographic progression in axSpA, and why you should consider sex and gender when managing patients with axSpA.a

High RF levels are considered a poor prognostic factor in RA, where patients are more likely to experience higher disease activity, more aggressive disease and higher risk of radiographic progression.16–19,41–43,a

Rapid radiographic progression (RRP), defined as an increase in Sharp/van der Heijde score (SHS) of ≥5 units/year, indicates a high rate of joint destruction.15,16,43 However, for patients with RA and RRP, early and intensive treatment can slow the rate of radiographic progression, altering the course of the disease.16 Identifying patients with RA at high risk of RRP is therefore critical for making appropriate treatment decisions.16

A range of clinical and biological markers have been identified as baseline risk factors for the progression of joint damage in patients with RA, and combining markers can improve their predictive power.16

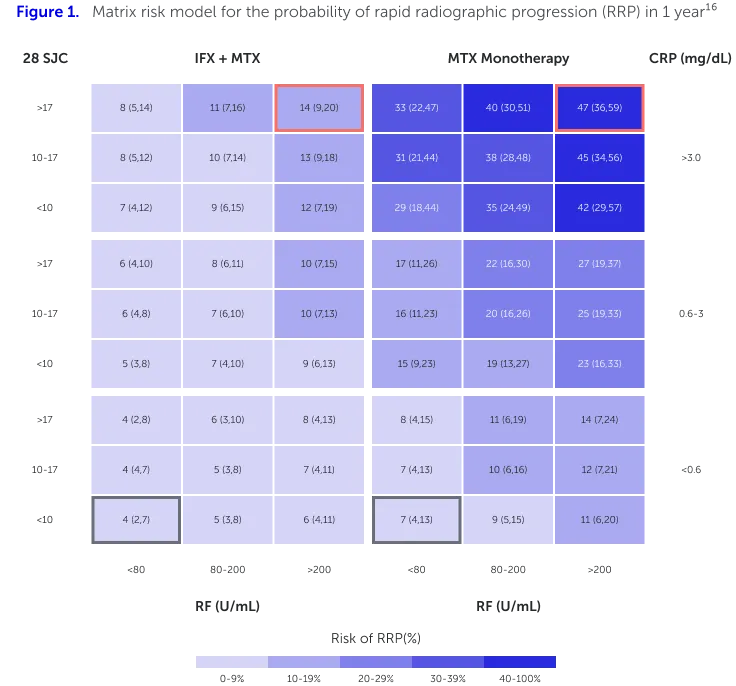

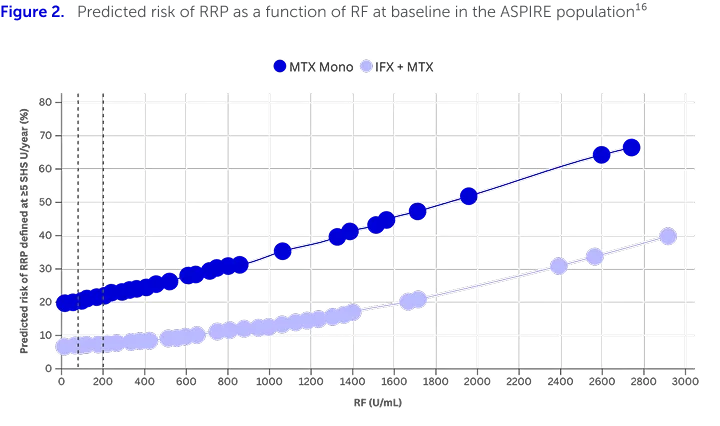

With the aim of predicting risk of RRP, an exploratory prediction model has been developed using the ASPIRE early RA study population (n=1,049), who were treated with either methotrexate (MTX) or infliximab (IFX) plus MTX.16,b The model’s method for outcome prediction was also tested in the ATTRACT established RA study population (n=428), who were treated with either MTX monotherapy or IFX plus MTX.16 The matrix model illustrated how levels of RF, C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and swollen joint count (SJC) relate to the probability of RRP (Figure 1).16

Matrix risk model for the probability of RRP in 1 year including all selected baseline risk factors except ESR, generated from the ASPIRE early RA data set (n=1,049). The numbers in each cell represent the percentage (95% confidence interval [CI]) of patients who had RRP out of all patients who have the baseline characteristics and receive the initiated treatment as indicated. Higher percentage indicates more severe radiographic progression of joint damage.16

Adapted from Vastesaeger N, et al. 2009.16

|

|

The study further categorised the risk factors into disease activity-related factors (CRP, ESR and SJC) and serological factors (RF levels). When investigating serological factors, the predicted risk of RRP was found to increase with baseline RF levels (Figure 2).16

n=1,049. Dotted vertical lines represent the selected ranges for RF (<80, 80–200 or >200 U/mL). Higher percentage indicates more severe radiographic progression of joint damage.16

Adapted from Vastesaeger N, et al. 2009.16

High RF levels (>200 IU/mL) were associated with increased risk of RRP in patients with RA treated with IFX+MTX or MTX monotherapy (Figures 1 and 2).16,aThis preliminary matrix risk model uses established disease characteristics (RF, SJC, CRP or ESR) that are readily available in routine clinical settings, to generate easy-to-use, visual matrices that, once refined through future development, can be used to predict the risk of joint damage progression in RA patients.16 |

ADDITIONAL MATRIX MODELS In 2020, a post-hoc analysis aimed to develop a new matrix to estimate the risk of RRP for patients with early RA after one year.43 Data from cohorts and several randomised clinical trials (RCTs), including ASPIRE, were pooled (n=1,306) to obtain RRP probabilities for different baseline characteristic combinations.43,c This updated matrix estimated RRP probability for 36 combinations of baseline characteristic levels, with greater precision compared to previously published matrices.43 In this matrix, RF positivity was retained as a predictor for RRP (odds ratio [OR] 2.1, p<0.001), alongside presence of structural damage at diagnosis, SJC and CRP levels.43 |

CONCLUSION

In exploratory risk models of RRP risk in RA, RF was identified as an important predictor of radiographic progression, alongside disease activity-related factors such as CRP, ESR and SJC.16,41,43

Hear from the experts: with Prof. Salvatore D’Angelo

While the burden of radiographic progression is high for both patients with RA and patients with axSpA, the clinical presentation of structural damage is different across the two diseases.3,8–11 In the video below, Prof. Salvatore D’Angelo explores the differences between radiographic progression in axSpA and RA, and the implications for clinical practice.

“Although progression from non-radiographic to radiographic axSpA is usually slow, the resulting structural damage can deeply affect patients’ physical function and their overall quality of life”

Prof. Salvatore D’Angelo

San Carlo Hospital, Potenza, Italy

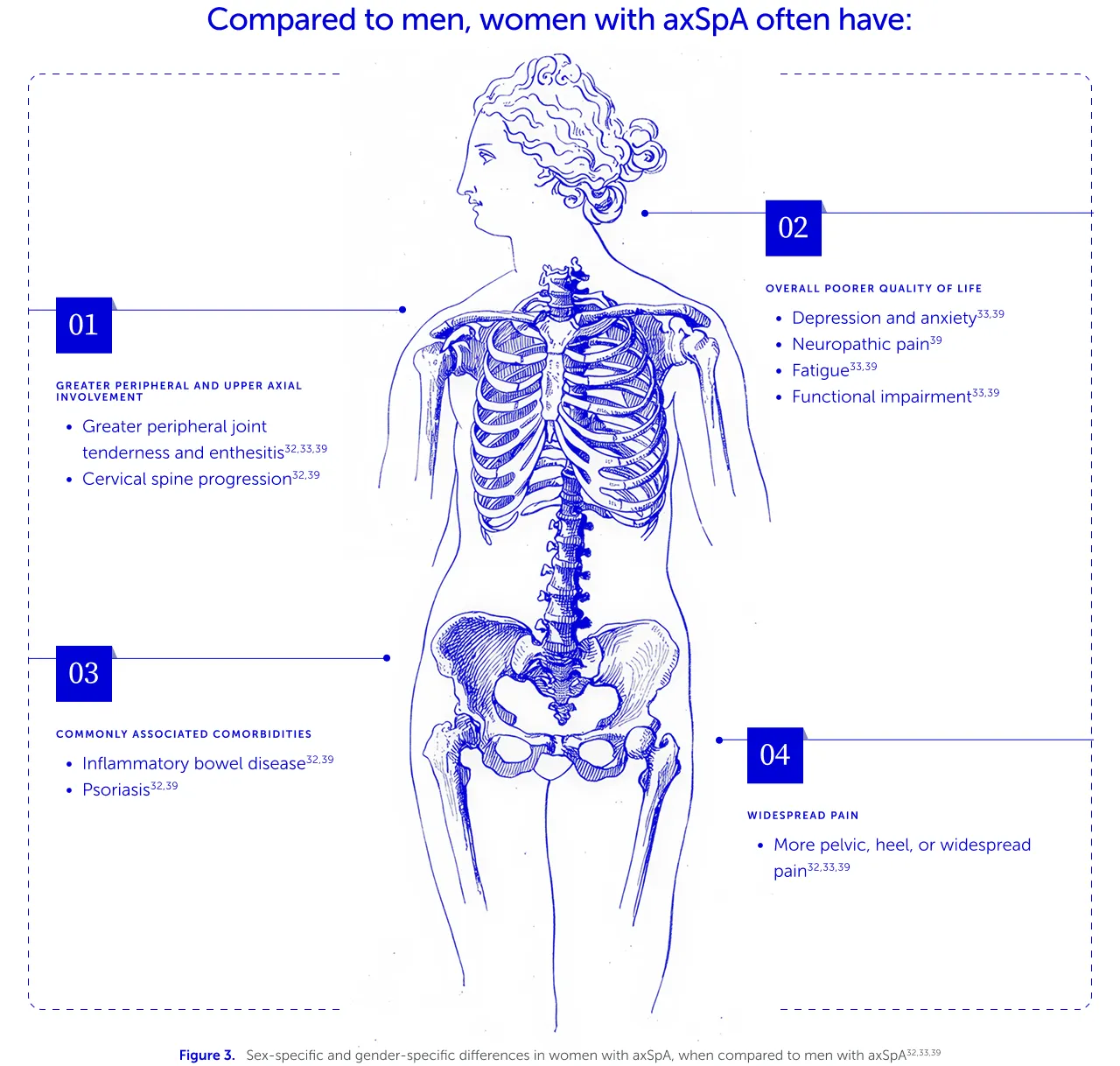

For patients with axSpA, diagnostic delays are associated with increased burden of disease and worse clinical outcomes, particularly in relation to mobility and physical function.44,45 Furthermore, women with axSpA experience a different range of symptoms compared to men (Figure 3), which can impact the speed of diagnosis and their overall treatment journeys and outcomes.7,31–33 It is therefore crucial to understand the differences in axSpA presentation for women compared to men, to support earlier diagnosis and treatment, and therefore optimise treatment outcomes.7,39,44,45

For example, women with axSpA experience greater limitations in physical function, as they report greater peripheral and upper axial involvement.32,33,39 This contributes to greater stiffness, loss of mobility and reduced quality of life.32,33,39 While they tend to have slower radiographic progression and less structural spinal damage compared to men, women tend to report more widespread pain than men, which can be misdiagnosed as fibromyalgia, contributing further to diagnostic delays.32,33,39

| Due to differences in symptom presentation and a lower prevalence of radiographic changes, female patients with axSpA experience a greater diagnostic delay compared to male patients (mean of 8.2 years vs 6.1 years across European countries).31–33,39,40 |

Delayed axSpA diagnosis is associated with greater functional impairment, higher healthcare costs and worse quality of life for patients.44 Importantly, a longer diagnostic delay was also identified as a negative predictor for positive response to biologic treatment.32 Studies have indicated that women with axSpA have significantly lower efficacy, response rate and drug survival for anti-TNF treatment compared with men.31–33,46

A reduced response to biologic treatment can be a particular concern for women of childbearing age with axSpA, as the risk of disease flares during pregnancy increases if treatment is interrupted.47 Stopping treatment during pregnancy could also jeopardise disease control and lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with chronic rheumatic conditions.35,37,47

It is therefore important for healthcare professionals to discuss future family plans with their female patients with axSpA at treatment initiation.34–36,48,49 As ~50% of pregnancies are unplanned, these conversations need to occur frequently and start early to help women make informed treatment choices that allow continuity of treatment and continued disease control for all potential family plans.34–36,48,49

CONCLUSION

Earlier identification of symptoms according to sex and gender could enable earlier diagnosis and treatment for women with axSpA, which is pivotal for optimising treatment outcomes.7,32,33,45,46 Early and continuous treatment, supported by frequent discussions with healthcare providers around family planning, is especially recommended for women of childbearing age to minimise disease activity and reduce the impact of disease progression.34–38

Other articles you might like

You can read more articles that might interest you.

Achieving clinical remission for your female patients of childbearing age (aged 18–45)

Explore the potential implications of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) molecular structure on placental transfer

Want to see more articles?

Can’t find the answer you’re looking for? See all the Resources we have.

GL-DA-2500838

Date of preparation: December 2025

Explore factors impacting RA and axSpA management, such as radiographic progression, and sex and gender differences.